By: John Roach, March 23, 2018

We are in a tavern in Stoughton.

There is a Viking canoe just off to our right with smoke wafting from the nose of the dragon on its bow. These Norwegians are absolutely crazy.

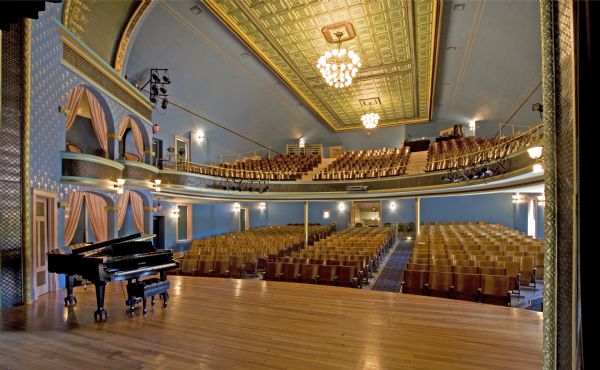

Our gaggle has gathered to attend a concert at the Stoughton Opera House, as fine a little entertainment venue as you will ever enjoy. We have come to watch a group of working Madison musicians do their thing in homage to a band for the ages: Steely Dan. The Madison act smartly calls itself Steely Dane. My millennial daughters jumped in at the last moment to join us. Seems they like “My Old School,” too.

For two hours, 10 of us sing from the balcony as the musicians slay the work of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker. The maestro and chief arranger, Dave Adler, cavorts about the stage. Behind him, Dave Stoler, Thomas Mattioli, Phil Lyons and others bring the groove and funk as Biff Blumfumgagne, Al Falashci, Jay Moran, Courtney Larsen and others take turns singing lead vocals. The large ensemble fills the hall with soul and smarts.

It is a big band with a big sound, and it is damn near perfect.

For some reason I am truly moved by the work of these musicians. These are men and women who live among us and do something that isn’t easy: They make a living in the arts. Some of them augment their cash flow with day jobs as teachers, computer programmers and the like. But on this night, on that stage, they seemed to be doing exactly what they were meant to be doing with their lives. Being artists.

Making a living in the arts is a tricky proposition. It’s the news parents don’t want to get from their kids upon college graduation. It’s a high-risk proposition when they announce they want to act, sing, play, compose, write or draw.

For more than four decades the arts have been my lot, both commercially and otherwise. I’ve counseled a lot of young folks on whether to pursue an artistic career, always telling them to take their shot — because if they don’t, it will haunt them. And if they fail, and they have to follow a straighter occupational route, they will be shocked at how much they learned as a working artist, with a body of knowledge and experience that can be applied to any business field. But I always tell them to try.

Because whatever they are feeling, the life of an artist is calling to them. They have to heed that call while they are young and free of a spouse, offspring and a mortgage. If they don’t heed it, all they will own is regret.

A life in the arts is viewed by many as risky, because so many folks view it as an all-or-nothing play. You go to Hollywood and you become Jennifer Lawrence or Ryan Gosling, or not. But the arts offer much more opportunity than the palm trees of Hollywood.

Madison is full of agencies and departments that pay artists to write, direct, draw, edit, design or photograph. According to the National Endowment for the Arts, there are more than 2.1 million workers employed nationally in the arts, with a high percentage of them being self-employed entrepreneurs.

In my early life I had a lot of different jobs. Some of them were fun. Some weren’t. But none compared to the moment I got my first job as a writer. Ever since that day decades ago, I’ve never looked at a clock at work.

So many folks spend their lives, in Jackson Brown’s words, struggling “for the legal tender,” doing work that they endure for the sake of family and lifestyle. But in their hearts, it’s not much more than a mercenary act. But then there are others who get to do the work they are meant to do.

And that’s the way it looked for the artists at the Stoughton Opera House. None of them were watching the clock. They were having too much fun. When waxing about working in the arts to friends, staff or students, I always fall back to a line I like. I tell folks that, like the gang in Steely Dane, I’m lucky. Because, as a working artist, what I do is who I am. How great is that?